External vs Internal Validity

External validity means how well a trial applies to patients we encounter in the clinic. Many trials enroll relatively young patients with minimal morbidities and good social support systems. While this may not exactly be a random sample of a population, we do not believe it to be nefarious.

A clinical trial generates an average treatment effect for that special population. If it is too selective, a clinician may have difficulty applying that effect to a typical patient. A good example are the seminal heart failure trials, which established so called guideline directed medical therapy. These trials enrolled hemodynamically stable patients mostly from an outpatient setting. One external validity concern is how well these effect sizes apply to less stable patients in the hospital.

Some trials are more pragmatic in design. The inclusion criteria are broad and procedures less strict than a standard trial. The advantage is that a pragmatic trial may be more applicable to real world practice. The disadvantage can be that it’s harder to prove the intervention is effective.

Internal validity refers to the degree of confidence that the causal relationship being tested in a clinical trial (i.e., Drug A compared to placebo reduces death in patients with acute coronary syndrome) is trustworthy and not influenced by other methodological factors. External validity refers to the degree of confidence that treatment effects from a study can be trusted if the intervention were to be provided to patients, with the same index condition (i.e., acute coronary syndrome), outside the confines of the study (i.e., real-world setting).

Factors that contribute to internal validity include random sequence generation and allocation concealment to minimize selection bias. An example of selection bias would be preferentially assigning patients to Drug A based on factors that predispose them to have better outcomes. In this case, differences in death between groups might be due to selection bias and not the effects of Drug A.

Other factors contributing to internal validity include blinding of participants and personnel to minimize performance bias; blinding of outcome assessment to minimize detection bias; incomplete outcome data predisposes the study to attrition bias; and selective reporting predisposes the study to reporting bias. (For example, performance bias can occur if one treatment arm receives more or less care than the other arm). If these factors are not all met, results from the clinical trial may be due to bias and not the causal relationship being tested. Thus, internal validity is of paramount importance.

The trials we review have had major impacts on the field of cardiovascular medicine. They were published in highly reputable journals by investigators or investigative teams held in high esteem by the profession. While some may still contain domains susceptible to bias (i.e., lack of blinding of participants and personnel for trials involving surgical or procedure-based interventions) they have generally met conditions deemed acceptable by the profession to be considered internally valid. Where issues with internal validity may exist, we will highlight them; however, in many cases, you won’t see it mentioned and that is why.

Is internal validity more important than external validity?

In our opinion, no, they are equally important.

There is tension between internal and external validity. You cannot have external validity without internal validity, but the opposite is not true. Some experts tend to elevate internal validity over external validity. We see no reason for this since internal and external validity are not mutually exclusive.

So why is external validity often limited? The reason is simple, to increase the chance of getting a positive result.

Without compromising internal validity, investigators can increase the chance of getting a positive result, by selecting a narrower and more homogenous group of patients with the index condition of interest and by being meticulous with how the intervention is administered and patients are monitored. This is done in the interest of minimizing treatment effect heterogeneity.

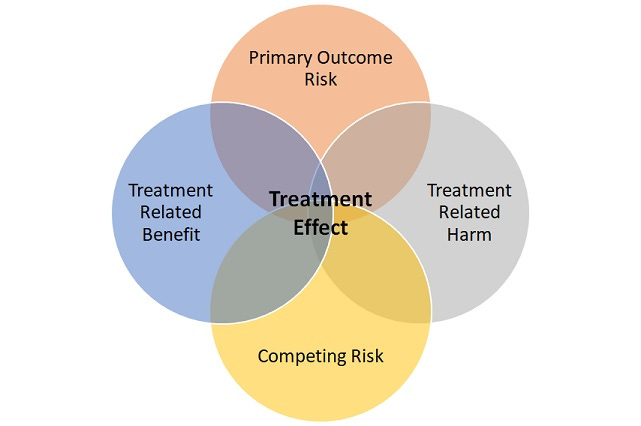

The idea is simple, find a group of patients with sufficient risk of experiencing the primary outcome to be able to show a difference and who are most likely to derive a direct benefit from treatment. Also, exclude patients likely to experience harm from treatment and who are likely to die or have events despite treatment (competing risk).

While this idea may seem controversial it is self-evidently true; otherwise, clinical trials, in general, would not enroll younger and healthier patients with less morbidities. In fact, the highly selective nature of trials is not even contested within the evidence-based medicine community.

If you accept the above idea is true, you may believe it to be nefarious, but we do not see it that way.

In our opinion, it is just a case of investigators and those who fund clinical trials responding to incentives, which are often but not always to prove efficacy. Thus, what we have in the world of medicine, where clinical trials are highly emphasized, are trials predominately conducted to prove efficacy.

Thus, it is the role of the clinical community to determine the extent to which the results of these trials are to be applied to patient care under real-world conditions. And that is where we begin.

We will soon publish our first review. It will be on the Beta-blocker Heart Attack (BHAT) trial. This is the first study in the Acute Coronary Syndrome section under Medicines.

Excellent start to the series. The potential conflict between internal and external validity may explain the disparity sometimes seen between results of clinical trials and real-world population-level impact.

I’m really looking forward to some critical thought process explaining why we do X instead of Y